The Systems-Driven Operator

How to Bring Clarity to Chaos in Sales Ops (and Become Indispensable in the Process)

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Problem: Too Much Structure, Not Enough Logic

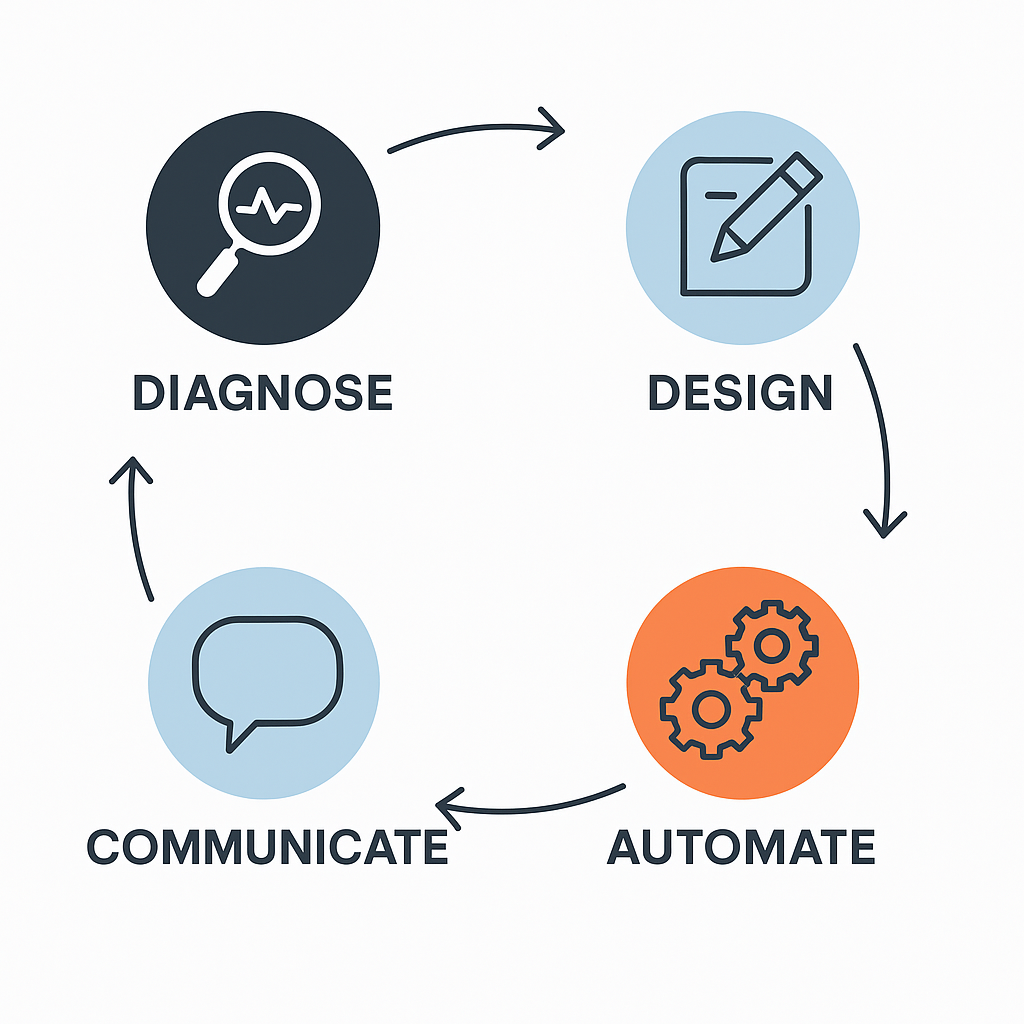

- The Systems Clarity Loop: Diagnose → Design → Automate → Communicate

- Step 1: Diagnose — Don’t Assume, Observe

- Step 2: Design — Build for the Way People Actually Work

- Step 3: Automate; But Only After You’ve Cleaned Up

- Step 4: Communicate — Loudly, Repeatedly, With Context

- Think Like a Systems Architect: Clarity is a Creative Act

- Avoiding the Traps

- Final Thoughts: The Operator as Architect

Introduction

Clarity is underrated.

You don’t really feel the pain of not having it until you’re 15 tabs deep in Salesforce, trying to explain to your VP why the pipeline numbers changed (again) between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m.

Then someone says, “It’s just a sync issue.”

It’s never just a sync issue.

Welcome to the jungle that is Sales Ops.

The Problem: Too Much Structure, Not Enough Logic

Most people think chaos is the absence of structure. Not true.

Chaos is what happens when too many structures are slapped together with no unifying logic. It’s not that there’s no structure. There’s too much of it—layered, bloated, and badly labeled.

Every well-meaning “let’s just add this field” turns into a long-term liability. Every new process, dashboard, and integration was once a solution. But they accumulate like barnacles on a ship. Eventually, the ship slows down.

Each new tool? A future ticket in the making. And somehow, despite all this infrastructure, nobody knows where the truth lives.

In high-growth environments, complexity is inevitable. But unmanaged complexity breeds chaos. That’s where things fall apart.

Your job (our job) is to cut through the noise and bring clarity. That’s the work. That’s the edge.

Here’s how I think about it.

A systems-driven operator creates clarity by diagnosing complexity, designing human-centered solutions, automating with intention, and communicating with precision.

This work is not just functional. It’s creative, strategic, and essential to sustainable growth.

Here’s the thing: Most ops problems are not tech problems. They are thinking problems disguised as tech problems.

The Systems Clarity Loop: Diagnose → Design → Automate → Communicate

Before you start tweaking fields in Salesforce, rolling out a new tool, or building another dashboard, you need to step back.

You bring clarity by looking at the system before you change it. Before you implement. Before you automate. Before you audit.

You ask: What is actually happening here, and why?

I call this the Systems Clarity Loop.

It’s a simple but powerful framework that defines how high-functioning operators work:

- Diagnose: figure out what’s actually happening

- Design: build workflows people will actually use

- Automate: with intention, not just because you can

- Communicate: loudly, clearly, and often

Each one matters. Each one builds on the last. Skip one, and your elegant system becomes another mess someone else has to untangle later.

Diagnose. Design. Automate. Communicate.

My goal is to provide a practical, flexible framework to diagnose disorder, design smarter workflows, automate with intention, and communicate with precision.

Let’s walk through it.

Step 1: Diagnose — Don’t Assume, Observe

Symptoms Are Not the System

Before you implement. Before you automate. Before you audit.

You have to see.

You can’t fix what you haven’t actually looked at.

Start by looking, really looking. What is actually happening on the ground? Map the flow of work, not how it was supposed to work, but how it really works.

Ask dumb questions. Interview users like an anthropologist. Audit the systems, the fields, the rules, the reports.

Before you jump into fixing, building, or automating, stop. Watch. Ask. Map. In many orgs, the stated system (how things are supposed to work) and the actual system (how things actually work) are misaligned.

You’re not there to validate what leadership thinks is happening. You’re there to find what actually is.

Why most ops projects fail early:

- They assume the system works the way leadership thinks it does

- They chase surface-level symptoms (e.g., “We need better reporting”) without investigating root causes

- They rely too heavily on tools and not enough on user behavior

I’ve seen ops teams run full-speed into “solutions” that had nothing to do with the real issue. The problem isn’t the reporting. The problem is a legacy workflow that’s been quietly wrecking your funnel for months.

Your job in this phase is not to solve. It’s to observe.

Identify bottlenecks. Surface redundancies. Find where things break, where people double-handle, where steps are skipped. Capture not just the what, but the why.

Real diagnosis means you:

- Shadow people. Sit with reps, managers, Ops colleagues. Listen to what they do and what they skip. Write it all down.

- Sit in on forecast meetings. Just listen. Where does tension show up? Where does data get questioned?

- Audit the system. Not the pretty layer; the actual fields. What’s used, what triggers automations, what’s been forgotten?

- Sketch the workflow. I don’t care if it’s Miro or a napkin. Start with “Deal Created” and follow the thread to “Closed Won/Lost.”

- Ask why. Over and over. Why do we do it this way? Who set this up? What breaks when we change it?

The Three Histories of Every Broken Workflow

- Someone left and didn’t document it

- Someone still here built a workaround they forgot about

- Someone bought a tool without looping in anyone from Ops

Real example: I once consulted on a Salesforce instance where the sales team insisted Salesforce was “slow and buggy.” It had seven flows triggering on opportunity creation. Seven. One of them pinged a deprecated tool no one had access to. It took weeks to unwind. No one remembered building it.

Diagnosis is slow upfront. But it saves you from spending three months fixing the wrong thing.

This is where your process map, revenue blueprint, or painstorming sessions come in. This is where operators earn trust; not just by mapping how things should work, but by listening for friction, workarounds, and mismatches.

Now that you understand what’s really happening, it’s time to design what should happen; based on how people actually work, not how we wish they did.

| Key takeaway: You can’t fix what you don’t understand. Build a diagnostic muscle before reaching for solutions. |

Step 2: Design — Build for the Way People Actually Work

Build for Humans, Not Hypotheticals

Design is about trade-offs. Not perfection.

You’re not designing a system to make Salesforce happy. You’re designing a system to make people better at their jobs.

This is the heart of human-centered operations: systems that serve people, not the other way around.

Design is where most operators jump in. But without diagnosis, you’re designing in the dark.

That means:

- Building for real workflows, not imaginary ones

- Designing with context-switching, incentives, and attention spans in mind

- Collaborating with reps and managers before you ship

Once you have that clarity, you can begin crafting elegant, functional systems grounded in the reality of how your users behave.

Here’s a thing I believe: If your system only works because people follow a 12-step training doc, it’s not a good system.

A good system teaches the user as they move through it. It nudges them, guides them, and makes the right action the easiest one.

That’s what I mean by design.

It’s easy to forget that no system is neutral. Every flow nudges behavior. Every field shapes incentives. Every dashboard suggests what matters.

Design with constraints in mind. Technical debt. Change management fatigue. Executive attention span. Focus on leverage: what are the 1–2 changes that will ripple positively across the organization?

Let’s say reps are skipping fields in your lead process. Do you:

- Add validation rules and mandatory fields?

- Design a process that aligns better with how they actually qualify?

Most ops leaders choose #1. Great operators choose #2, and then revisit #1 if needed.

Build from first principles. Every field, rule, automation, and report should have a clear reason for existing.

What great operational design prioritizes:

- Simple over smart

-

- The smartest system in the world is useless if people don’t use it. If a rep has to open four tabs to close a deal, your process is bloated.

- Defaults over decisions

-

- Reduce choice. Nudge behavior. Don’t ask reps to choose a lead source from 15 options.

- Guardrails over gates

-

- Let people move fast, but keep them out of the ditch.

- Consistency over cleverness

-

- Naming conventions, field logic, onboarding steps; keep them tight.

You are not designing for the perfect version of your team. Design for the 80%. Let the 20% find manual workarounds if they need to.

If you try to solve for every edge case, you’ll build a nightmare.

Tactical design principles

- Reduce friction: Fewer clicks. Fewer fields. Fewer exceptions.

- Design for 80% of use cases: Create fallback paths for edge cases, but don’t let them dictate structure.

- Reinforce behavioral nudges: Use validation rules, dependent fields, and automation logic to guide desired behavior.

- Build atomic components: Think in reusable modules—e.g., a single lead scoring logic used across forms, SDR flows, and MQL dashboards.

- Design for errors. What happens when someone forgets to fill a required field? Do they get an error that makes sense? Or just “Validation Rule XYZ Failed”?

I once restructured a quoting flow that had twelve required fields. Reps hated it. Nobody used it. They hacked it with Google Sheets.

I cut it down to four required fields, moved two others behind a dependent picklist, and built a one-click approval rule based on deal size.

Result? Adoption shot up. Time to quote dropped by 60%.

Good design isn’t about making things “clean.” It’s about making them work better. Good process design reduces resistance and decision fatigue. It guides the human, not just the data.

With a design that reflects real behavior, we’re ready to scale its impact; intentionally, and only where it makes sense. It’s time to automate/

| Key takeaway: Human-centered design in ops means creating processes people want to use, not just ones that technically work. |

Step 3: Automate; But Only After You’ve Cleaned Up

Amplify the Good, Not the Broken

Automation is ops candy. Everyone wants it. “Can’t we just automate that?” they ask?

Sure, but here’s the thing: if the process is broken, automation just breaks it faster.

This means if your process is garbage, automation just spreads the stink faster.

Automation doesn’t fix chaos. It multiplies it—faster, and with fewer warning signs.

I’ve seen so many setups where one small change triggers a cascade of failures. You change a picklist value, and suddenly 14 flows fail because they weren’t updated. Or worse, nothing breaks; but the wrong data gets written silently for weeks.

The goal isn’t to automate everything. The goal is to automate what matters: those repeatable, low-risk tasks that you’ve already pressure-tested.

You automate to:

- Eliminate low-value tasks

- Reduce human error

- Codify and scale a working process

Only once you have a clear, user-centered design should you begin to automate.

My Rule of Thumb: If you can’t explain the logic in plain English, don’t automate it. Test it. Walk someone else through it. If they’re confused, you’re not ready.

You don’t automate to:

- Enforce compliance on a broken flow

- Mask underlying misalignment

- Impress stakeholders with complexity

Automation Traps to avoid

- Mystery logic. If no one knows what triggers an action, you’ve got a black box. That’s a red flag.

- Tightly coupled flows. One small change should not break the whole system.

- No ownership. Someone needs to own every single automation. If it breaks, who fixes it?

Best Practices

- Keep automations modular (use flows, not monoliths):

- Build in alerts and failsafes

- Document ownership and logic

- Make it easy to unwind or update later

Automations I Recommend

- Auto-close stale opps. Reps rarely clean their pipeline, and you know it. Build a quiet workflow that does it for them.

- Hot lead notifications (alert reps When prospects hit specific thresholds)

- Lead-to-account matching. If you’re not doing this yet, start yesterday.

- SLA alerts (5 minutes before breaking, not after)

Before you push anything live:

- Write a simple “When X, then Y unless Z” for each rule

- Test it in sandbox before deploying live (especially when automation impacts revenue workflows.)

- Schedule quarterly reviews, because all systems rot eventually.

Think of automation as delegation. You’re giving work to a machine instead of a person. That means you still need to define the job to be done, track whether it’s being done well, and maintain accountability for outcomes.

Just like with people, you still need training, documentation, and accountability.

Once you’ve scaled your process, it’s time to let people know. That’s right. It’s time to step away from your computer and communicate.

| Key takeaway: Automation doesn’t solve broken processes. It scales them. |

Step 4: Communicate — Loudly, Repeatedly, With Context

Storytelling Is the Operating Manual

The final step, and often the most overlooked, is communication. A system people don’t understand is a system they don’t trust.

As an operator, part of your role is translation: turning backend logic into frontend clarity. You’re not just the builder; you’re the narrator.

This is where most ops folks drop the ball. They build something great, then forget to tell anyone how or why it works. And surprise—the team goes rogue or ignores it.

Your job isn’t done until the story is told.

Good ops communication looks like:

- A diagram that shows how leads actually move through the funnel

- A Loom video explaining the logic behind your marketing dashboards

- A training session for managers on how to use your pipeline stages

You have to narrate the system. Explain what changed. Show why it matters. Teach people how to use it. Create dashboards that actually tell a story. Write documentation that people will use. Build internal trust by being transparent about trade-offs.

And the tone matters. If your enablement doc reads like it was written by a robot, it’s going to be ignored. Write like a human.

The operator’s job doesn’t end at implementation; it extends into enablement, storytelling, and strategic visibility. You must make internal systems narratable, so every stakeholder can understand what’s happening, why it matters, and how to act.

Why communication matters:

- Prevents shadow systems: When people don’t trust or understand the process, they build their own.

- Enables adoption: Especially for frontline teams who don’t care about architecture: they care about speed and clarity.

- Builds internal trust: Transparency in systems builds confidence in decisions.

Here’s a framework I lean on:

- Problem: What friction were we solving?

- Change: What’s new or different?

- Impact: How does it affect you?

- Action: What do you need to do next

Tools that Actually Work

- Monthly “Changelog” emails with context, impact, and clear instructions

- Loom walkthroughs for anything more than two steps (nobody reads PDFs anymore)

- Visual maps of your flows in Notion or Confluence

- Internal office hours to gather feedback and reinforce training

Also, name things clearly. If a flow is called “Lead Automation Flow 3 Final,” you’re asking for trouble.

Communication creates systems resilience. If you’ve built with transparency and logic, and explained the why, your systems are easier to adapt, evolve, and defend.

Bonus tip: Translate automation logic into simple language. If your VP of Sales can’t explain your lead scoring logic at a dinner party, it’s too complicated

| Key takeaway: The system only works if everyone understands it. Communication is your most underrated ops skill. |

Think Like a Systems Architect: Clarity is a Creative Act

Mastering these four steps is just the beginning. The real transformation happens when you begin to think like a systems architect.

This is the part they don’t tell you about Ops: it’s not just logistics. It’s strategy.

Systems thinking is imagination in action. You’re not just fixing workflows; you’re redesigning how work happens. The best operators reimagine systems, not just repair them.

The Best Operators Ask Better Questions

- What are we optimizing for?

- Where are we leaking time or trust?

- What are we unconsciously incentivizing?

- What failure modes are we inviting?

- How do we make this system more legible?

What creative systems thinkers do:

- Zoom out before zooming in: Understand the full context before tweaking a rule.

- Think in flows, not features: Tools come and go. Outcomes are what matter.

- Design for change: Build systems that evolve rather than break.

- Create maps, not mazes: Good systems create confidence, not confusion.

The goal? Build systems that make good behavior easy, bad behavior hard, and great work visible.

At its best, systems thinking is generative; designing a world that works better. This requires imagination alongside logic, and narrative alongside data.

This is why I often sketch systems on paper before I build them. Or explain a workflow to a non-technical colleague to test its clarity. It’s also why I obsess over naming conventions, error messages, and the onboarding experience.

These are small signals that communicate the intentionality behind the system, and that builds trust.

In an org I consulted on, I noticed that reps were emailing managers for quote approvals even though they had a tool for it. Why? Because the tool took too long and no one trusted the thresholds.

I rebuilt the approval matrix with a fallback rule. Deals under $10K? Autopass. $10–25K? One manager. Above that? Exec review.

Approval times dropped. Close rates improved. And, bonus, they finally had clean data on pricing exceptions.

It wasn’t a “tech fix.” It was a system redesign based on how people actually behave.

That’s systems work. And it’s the fun part.

| Key takeaway: Systems thinking is not just analytical—it’s imaginative. |

Avoiding the Traps

There are three common traps I see:

1. Over-Tooling

More tools do not equal better operations. They often introduce new failure points and increase cognitive load.

The best operators ruthlessly audit their stack and aren’t afraid to deprecate.

Questions to ask:

- Is this tool solving a real, current problem?

- Do we have adoption beyond the pilot group?

- What would break if we turned this off tomorrow?

2. Dashboard Theater

It looks pretty, but no one uses it. Dashboard theater happens when we build for optics, not action. A useful dashboard changes behavior. If it doesn’t, it’s noise.

Tips to fix it:

- Start with the decision you want the user to make

- Limit each view to one core question

- Annotate charts with insights, not just data

3. The Bus Factor

If a key part of your system only lives in one person’s head, you’re vulnerable.

The “bus factor” is how many people can get hit by a bus before the system breaks. Your job is to lower that risk.

Mitigations:

- Centralized documentation

- Shared schema maps

- Runbooks for key workflows

- Biweekly peer reviews of automation logic

Final Thoughts: The Operator as Architect

Sales Ops isn’t a back-office job. Not when you do it right.

The best operators are architects, translators, and storytellers who design how business runs; not just support it. They’re the architects of growth, the calm in chaos, asking “What’s really happening here?” before building something better.

Sales Ops isn’t about dashboards. It’s about building trust.

When you get this right:

- Leadership trusts you

- Frontline teams become more effective

- Finance works with accurate data

- The business grows faster, smoother, and smarter

You stop being the person who “handles requests” and start becoming the person who designs the machine. That’s the operator people remember.

So don’t aim for “polished.” Aim for clear. Don’t chase the shiniest tool. Chase understanding.

Build systems that work. Build processes people understand. Build clarity into every part of the business.

The Systems-Driven Operator’s Edge

You don’t need 30 automations, 5 dashboards, and 15 reports to prove your value.

You need:

- A loop: Diagnose → Design → Automate → Communicate

- A mind that sees systems, not symptoms

- The courage to pause before building

- The humility to watch before fixing

This is how you bring clarity to chaos, and become indispensable.

If I had to define Sales Ops in one sentence, it would be this: We build the scaffolding that enables sustainable growth.

This scaffolding must be sturdy yet flexible, growing with the company rather than constraining it. Most importantly, it must be human, because every system serves people with their quirks, goals, habits, and hopes.

Bringing clarity to chaos requires care and stewardship. It elevates the operator from backstage fixer to visible strategist; someone who makes the complex simple, the invisible visible, the fragile antifragile.

That’s the work. That’s the invitation. That’s your edge.

|

TL;DR: The Systems Clarity Loop

Big Idea: Ops problems are thinking problems; not tech problems |

If this resonated, I’ve got more where this came from:

- Here’s a tactical checklist to bring clarity into your systems, communication, and leadership practices.

- Here’s a cheatsheet of 10 tactics to operationalize clarity today

- How to Audit Your Salesforce Instance Without Going Insane

- The Anti-Theater Dashboard Template

- How to Run a Quarterly Workflow Review

Your turn: what’s the worst ops mess you’ve ever had to clean up? And how’d you fix it?

Like this? Share it with someone drowning in their CRM.