Becoming, by Michelle Obama

Publisher : Crown (2018)

ISBN-13 :978-1524763138

Rating:

Table of Contents

Quick Thoughts

Growing up African American on the south side of Chicago, Michelle Obama is a planner, smart, detail-oriented, and ambitious. She likes to check the boxes. She’s got goals and life plans that involve becoming an equity partner at her law firm before the age of 32. She prefers her life to be orderly and organized. And then she meets Barack Obama, a laid back, charming, intellectual Hawaiian of mixed race, whose outsize talent and ambition seem virtually purposefully designed to derail those needs. It’s almost a rom-com meet cute except these two people become the first African Americans to hold the position of President and First Lady of the United States.

Summary

Becoming goes into the canon of outstanding literature. It is a tour de force; an intimate look into the process of how a black woman growing up middle-class in the Southside of Chicago becomes an Ivy-league educated attorney, a reluctant political spouse, and the first African American First Lady of the United States. Truthfully, the portion of Becoming that covers Michelle Obama’s time in the White House is not even the most interesting part of her biography. Michelle Obama’s time as FLOTUS only actually occupies about 5 of Becoming’s twenty-four chapters.

The majority of Becoming is about what it takes to grow up black and female, invisible, often underestimated, the weight of expectations, the challenges of merging ambition with marriage and motherhood, struggles with fertility, overcoming self-doubt, finding meaning in life, and what it means to leave the door open for others. It’s an exploration of what it takes to merge the ambitions of two smart, hardworking, and talented performers within a modern marriage.

Becoming is also about the process of growing up; how the process is never actually quite complete. To become is to transcend the self; to never give up on the idea of growth and optimism. To be uncynical about humanity. And, to have faith in the unlimited potential within yourself and other people. It’s a deeply personal and intimate look into the historic nature of Barack and Michelle Obama, the first African-Americans to be President and First Lady of the United States of America. What it means to be a symbol of hope for millions, and of fear for others. And, as Michelle Obama observes, “I’m an ordinary person who found herself on an extraordinary journey. In sharing my story, I hope to help create space for other stories and other voices, to widen the pathway for who belongs and why. (455)

This is Michelle Obama’s story of her becoming. I’d recommend this book to women, to women who are trying to have it all, to minority women, and to people who would like to gain a more insightful understanding of the female and black experience in the United States. I’d recommend this book to everyone.

3 Main Ideas

- We are always in progress. There is no finished final state for a human being, and nothing is set in stone. We can always choose to learn, grow, and transform. We are always in the process of becoming. “Becoming is never giving up on the idea that there’s more growing to be done.” (453)

- It’s important to have early advocates and mentors, especially when children are young and impressionable. Having someone who believes in you and encourages your talents enables one to gain confidence and persist, even in the face of overwhelming obstacles. Michelle Obama’s high school guidance teacher told her she wasn’t Princeton material. But, thanks to the love and care instilled by her parents, Michelle Obama did not allow those low expectations to dampen her confidence in herself. Sometimes, those obstacles can even serve as fuel for determination and achievement.

- Developing self-confidence is important in helping one to find their meaning, purpose, and to becoming authentically themselves. Several times throughout Becoming, Michelle Obama repeats that failure begins in the mind. “Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result.” Conversely, then, success also begins in the mind. She says that the antidote to defeating thoughts of failure that preempt actual failure is to develop a strong sense of confidence. You must improve your mindset and believe in yourself: “Confidence …sometimes needs to be called from within. I’ve repeated the same words to myself many times now, through many climbs. Am I good enough? Yes I am.” (310)

5 Key Takeaways

- Race, Racism, and Belonging. As a black woman, Michelle Obama describes the multiple challenges to be found at the intersection of race and gender. There are many ways and spaces in which she found herself an outsider, an unexpected presence. From her undergraduate days at Princeton, where a roommate moved out rather than live with a black person, to the law firm where she was one of five African American lawyers in a 400-person law firm, and to the racial backlash triggered by Barack’s existence at the pinnacle of US political power. Michelle Obama describes the expectations placed upon her and her brother to transcend their hometown and its downward trajectory, but also being called out by a young relative for “talking white”. She describes the challenges faced by minority students at Princeton, including racism and other acts of microaggressions, in contrast to the oblivious privilege and confidence of the majority of the primarily white and male student body. And, in Barack Obama’s campaign for, and existence in the White House, the racism, and outrage that lay at the roots of Republican obstruction and the backlash to their existence in the White House. She writes: “As the only African American First Lady to set foot in the White House, I was “other” almost by default. If there was a presumed grace assigned to my white predecessors, I knew it wasn’t likely to be the same for me….My grace would need to be earned…. I stood at the foot of the mountain, knowing I’d need to climb my way into favor.” (310)

- Balancing Ambition in a Modern Marriage. “I’d been raised to be confident and see no limits, to believe I could go after and get absolutely anything I wanted. And I wanted everything. Because…why not?” (184) In a modern marriage with two-career parents, it is difficult to balance the demands of career versus the demands of marriage and parenthood among two ambitious individuals. “We were riding a seesaw, the two of us, the mister on one side and the missus on the other. ” (237) Even in a modern marriage, in a world that advocates for gender equality, and with a progressive husband like Barack Obama, women still bear the greater burden of balancing career, ambition, and family. Michelle Obama is highly educated, and ambitious. Yet, she makes the choice to step away from her career in order for Barack Obama to have his chance of realizing his purpose and ambition of creating the “world as it should be.” She offers insight into a modern marriage between two ambitious and talented individuals. A marriage that, while it isn’t perfect, is an example of two partners giving each other freedom to grow and pursue meaning.

- The Weight of Expectations. The role of expectations in achievement and identity are a major theme. Michelle Obama’s parents had high expectations of her and her brother. They were expected to achieve and transcend, and fulfil their family’s unrealized hopes and dreams. Both her grandfathers were denied jobs, education, opportunity, and excluded from high-paying union jobs due to their skin color. Her parents also did not receive a college education. All this family history and experience impressed upon the young Michelle the need to excel and make the most of all her opportunities, and to use education as a way to transcend and achieve. Michelle Obama also describes the low expectations that many people have of minorities, especially children of color. She explains how these low expectations can turn into self-fulfilling prophecies unless someone breaks the cycle or intervenes, or there is an advocate or mentor. “Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self-doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear. (51)

- The Power of Belief. Throughout Becoming, Michelle Obama is constantly plagued with self doubt, harboring fears about whether she is good enough. At one point, she is told directly (by her high school guidance counsellor) that she is not good enough (for Princeton). And yet, she is constantly bolstered by the self-confidence instilled in her by her parents, her love of learning, and her determination to persist in spite of overwhelming odds and challenges. Michelle Obama stresses the need to keep that inner voice in check, to have confidence in oneself and in one’s achievements. And to realize that self doubt is normal, and natural. Ignore people who have low expectations of you, who want to impose limitations on you; push yourself to excel, and place yourself in situations that lead to people who believe in your potential. Even the most accomplished and extraordinary people… “have had doubters. Some continue to have roaring, stadium-sized collections of critics and naysayers who will shout I told you so at every little misstep or mistake. The noise doesn’t go away, but the most successful people I know have figured out how to live with it, to lean on the people who believe in them, and to push onward with their goals.” (75)

- Education as Leverage. Michelle Obama cites education as the tool that helped her to transcend her failing neighborhood, and to achieve dreams that had been long denied to many of the members of her family. She cites her life and experience as an example of what people can achieve if they are provided with resources, confidence, and opportunity. For instance, her mother listened to Michelle’s complaint about her second grade classroom, and advocated for her; an action that led to Michelle being removed from a classroom with an inept teacher, and diverted into a better one with more resources. Equipped with that advocacy and opportunity, Michelle eventually tested into a third-grade class of high-performing children. Michelle Obama cites her mother’s involvement and advocacy as providing a crucial step in her success in school. And, by taking advantage of these resources, and working hard to prove herself, she excelled in class and other high performing environments. A good education provides leverage, regardless of one’s environment. What she maintains throughout Becoming is that she is not special; that many struggling neighborhoods are full of children just as smart and talented as her. They only need the chance to prove it.

Top Quotes

- For me, becoming isn’t about arriving somewhere or achieving a certain aim. I see it instead as forward motion, a means of evolving, a way to reach continuously toward a better self. The journey doesn’t end….It’s all a process, steps along a path. Becoming requires equal parts patience and rigor. Becoming is never giving up on the idea that there’s more growing to be done. (453)

- Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self-doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear. (51)

- As a kid, you learn to measure long before you understand the size or value of anything. Eventually, if you’re lucky, you learn that you’ve been measuring all wrong. (341)

- Confidence …sometimes needs to be called from within. I’ve repeated the same words to myself many times now, through many climbs. Am I good enough? Yes I am.” (310)

- As the only African American First Lady to set foot in the White House, I was “other” almost by default. If there was a presumed grace assigned to my white predecessors, I knew it wasn’t likely to be the same for me….My grace would need to be earned…. I stood at the foot of the mountain, knowing I’d need to climb my way into favor. (310)

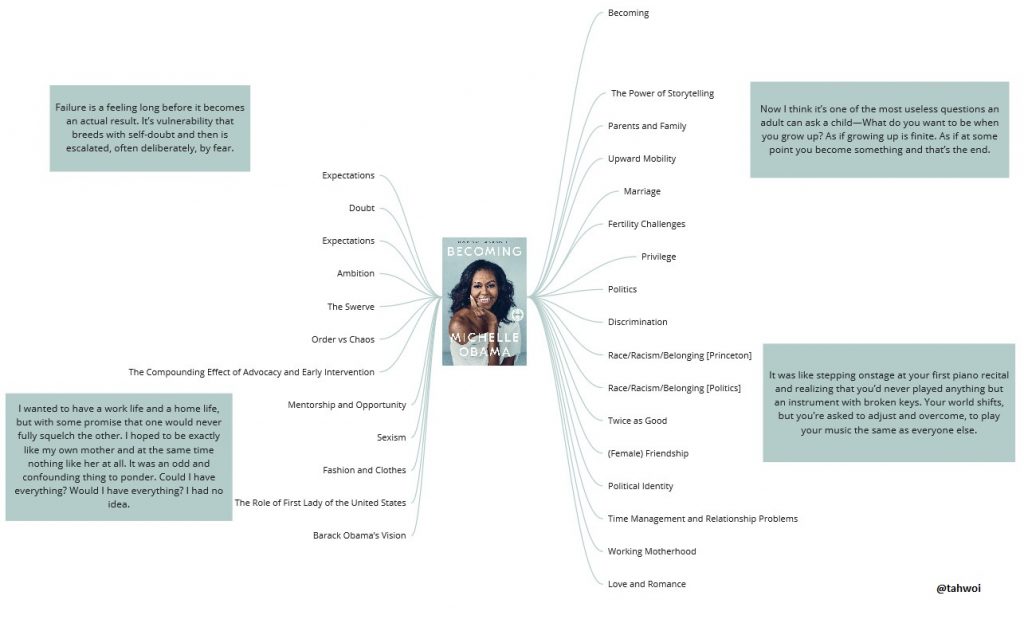

Mind Map

Structure

Becoming Me (Chapter 1 – 8)

- Chapter 1: Family, music, growing up on the south side of Chicago

- Chapter 2: Elementary education, changing neighborhood demographics of South Shore

- Chapter 3: Family, Dandy, racial discrimination and dreams deferred; upward mobility

- Chapter 4: Bryn Mawr Elementary Gifted and Talented program, blossoming adolescence, growing independence from parents, first kiss, state of parent’s marriage

- Chapter 5: family finances, affording Catholic school tuition for Craig, High school experience at Whitney Young, Craig departs for Princeton, college plans, doubts and expectations

- Chapter 6: Princeton, race and racism, affirmative action, privilege, belonging, overcoming doubts

- Chapter 7: family history and connection to the South, ambition, post-college plans, becoming a lawyer (Sidley & Austin)

- Chapter 8: meeting Barack Obama

Becoming Us (Chapter 9 – 18)

- Chapter 9: beginning to date and become serious, Barack’s family history and temperament, losing Suzanne

- Chapter 10: keeping a journal, Barack’s ambitions, the search for meaning, losing her father

- Chapter 11: proposal, search for fulfilment, meeting Valerie Jarrett, accepting a new job, visit to Nairobi, Kenya

- Chapter 12: marriage, project VOTE!, Barack’s first book and overcommitment, balancing family, career, and ambition

- Chapter 13: new job at Public Allies, The Hole, Dreams of My Father is published, Barack is elected to the Illinois state senate, Barack’s mother dies of ovarian cancer, associate dean of community relations at University of Chicago; infertility challenges and IVF;

- Chapter 14: working motherhood; executive director for community affairs, University of Chicago Medical Center; time management, relationship challenges, couples counselling

- Chapter 15: work/life tradeoffs; 2004 DNC keynote address; Barack is elected to the US Senate for Illinois; the tradeoffs involved in agreeing to a Presidential run; Hurricane Katrina

- Chapter 16: campaigning for President; healthy eating for children as a possible interest; winning the Iowa primaries;

- Chapter 17: campaign lowlights; political sucker punches; racism in the media ; the need to protect oneself; campaign highlights

- Chapter 18: fears about the Bradley effect; the 2008 financial crisis; Barack’s grandmother dies; Barack Obama is elected as POTUS 44;

Becoming More (Chapter 19 – 24)

- Chapter 19: preparing to enter the White House; welcome by George and Laura Bush; conversations with previous first ladies; considering plans for her role as FLOTUS; inauguration

- Chapter 20: life in the White House, Barack’s first address to Congress, meeting Queen Elizabeth, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, working with children

- Chapter 21: a date in NY; forgoing spontaneity; clothing and fashion choices as a source of power and attention; the White House garden, Let’s Move! initiative

- Chapter 22: giving up control; chaos vs control; passing a child nutrition bill to expand access to healthy, high-quality food in public schools, White House mentorship program for young women; escaping the White House; Boot Camp with girlfriends at Camp David

- Chapter 23: expectations, visiting South Africa and meeting Nelson Mandela, the nature of progress; the Newtown, Connecticut mass shooting; Reach Higher initiative

- Chapter 24: wrapping up Barack’s second term in office; Mother Emanuel mass shooting; racial backlash to the Obamas; campaigning for Hilary Clinton in the 2016 election; reflecting on accomplishments; the power of stories; the meaning of America

Themes

Becoming

- Now I think it’s one of the most useless questions an adult can ask a child—What do you want to be when you grow up? As if growing up is finite. As if at some point you become something and that’s the end. pg. 5

- For me, becoming isn’t about arriving somewhere or achieving a certain aim. I see it instead as forward motion, a means of evolving, a way to reach continuously toward a better self. The journey doesn’t end….It’s all a process, steps along a path. Becoming requires equal parts patience and rigor. Becoming is never giving up on the idea that there’s more growing to be done. pg. 453

- For every door that’s been opened to me, I’ve tried to open my door to others. And here is what I have to say, finally: Let’s invite one another in. Maybe then we can begin to fear less, to make fewer wrong assumptions, to let go of the biases and stereotypes that unnecessarily divide us. pg. 455

- Maybe we can better embrace the ways we are the same. It’s not about being perfect. It’s not about where you get yourself in the end. There’s power in allowing yourself to be known and heard, in owning your unique story, in using your authentic voice. And there’s grace in being willing to know and hear others. This, for me, is how we become. pg. 455

The Power of Storytelling

- Your story is what you have, what you will always have. It is something to own. pg. 6

- Bear with me here, because this doesn’t necessarily get easier. It would be one thing if America were a simple place with a simple story. If I could narrate my part in it only through the lens of what was orderly and sweet. If there were no steps backward. And if every sadness, when it came, turned out at least to be redemptive in the end. But that’s not America, and it’s not me, either. I’m not going to try to bend this into any kind of perfect shape. pg. 411

- So many of us go through life with our stories hidden, feeling ashamed or afraid when our whole truth doesn’t live up to some established ideal. We grow up with messages that tell us that there’s only one way to be American….That is, until someone dares to start telling that story differently….. I had nothing or I had everything. It depends on which way you want to tell it. pg. 450

- I thought about America this same way. I loved my country for all the ways its story could be told. For almost a decade, I’d been privileged to move through it, experiencing its bracing contradictions and bitter conflicts, its pain and persistent idealism, and above all else its resilience. pg. 451

- I’m an ordinary person who found herself on an extraordinary journey. In sharing my story, I hope to help create space for other stories and other voices, to widen the pathway for who belongs and why. pg. 455

Parents and Family

- My father, Fraser, taught me to work hard, laugh often, and keep my word. My mother, Marian, showed me how to think for myself and to use my voice. pg. 6

- Even if we didn’t know the context, we were instructed to remember that context existed. Everyone on earth, they’d tell us, was carrying around an unseen history, and that alone deserved some tolerance. pg. 14,

- In general, they weren’t ones to intervene in matters outside schooling, expecting early on that my brother and I should handle our own business. They seemed to view their job as mostly to listen and bolster us as needed inside the four walls of our home. pg. 19

- My parents talked to us like we were adults. They didn’t lecture, but rather indulged every question we asked, no matter how juvenile. They never hurried a discussion for the sake of convenience. …They also never sugarcoated what they took to be the harder truths about life. pg. 33

- Preparation mattered. Our family was not just punctual; we arrived early to everything, ….The lesson being that in life you control what you can. pg. 40

- She loved us consistently, Craig and me, but we were not overmanaged. Her goal was to push us out into the world. “I’m not raising babies,” she’d tell us. “I’m raising adults.” She and my dad offered guidelines rather than rules. It meant that as teenagers we’d never have a curfew. Instead, they’d ask, “What’s a reasonable time for you to be home?” and then trust us to stick to our word. pg. 54

- You don’t really know how attached you are until you move away, until you’ve experienced what it means to be dislodged, a cork floating on the ocean of another place. pg. 86

Working Motherhood

- I’d been raised to be confident and see no limits, to believe I could go after and get absolutely anything I wanted. And I wanted everything. Because, as Suzanne would say, why not? pg. 184

- I wanted to have a work life and a home life, but with some promise that one would never fully squelch the other. I hoped to be exactly like my own mother and at the same time nothing like her at all. It was an odd and confounding thing to ponder. Could I have everything? Would I have everything? I had no idea. pg. 185

- There were certain small-scale projects I chose not to take on. There were young employees whom I could have mentored better than I did. You hear all the time about the trade-offs of being a working mother. These were mine. pg. 224

- If I’d once been someone who threw herself completely into every task, I was now more cautious, protective of my time, knowing I had to maintain enough energy for life at home. pg. 224

- But to me, it felt like the only sane choice. Something had to give. No one else could run my programs at the hospital. No one else could campaign as Barack Obama’s wife. No one could fill in as Malia and Sasha’s mother at bedtime. But maybe Sam Kass could cook some dinners for us. pg. 255

- I was a full-time mother and wife now, albeit a wife with a cause and a mother who wanted to guard her kids against getting swallowed by that cause. It had been painful to step away from my work, but there was no choice: My family needed me, and that mattered more. pg. 281

Financial Challenges/Upward Mobility

- My family, in fact, was probably on the poor side of the neighborhood spectrum. We were among the few people we knew who didn’t own their own home, stuffed as we were into Robbie and Terry’s second floor. pg. 28

- The idea was we were to transcend, to get ourselves further. They’d planned for it. They encouraged it. We were expected not just to be smart but to own our smartness—to inhabit it with pride—and this filtered down to how we spoke. pg. 48,

- My parents never once spoke of the stress of having to pay for college, but I knew enough to appreciate that it was there. pg. 68

- They were in their early forties then, married nearly twenty years. Neither one of them had ever vacationed in Europe. They never took beach trips or went out to dinner. They didn’t own a house. We were their investment, me and Craig. Everything went into us. pg. 68

- You’ve worked yourself out of that bus and across the plaza and onto an upward-moving elevator so silent it seems to glide. You’ve joined the tribe. At the age of twenty-five, you have an assistant. You make more money than your parents ever have. Your co-workers are polite, educated, and mostly white. You wear an Armani suit and sign up for a subscription wine service. You make monthly payments on your law school loans and go to step aerobics after work. Because you can, you buy yourself a Saab. pg. 102

Marriage

- I understand now that even a happy marriage can be a vexation, that it’s a contract best renewed and renewed again, even quietly and privately—even alone. I don’t think my mother announced whatever her doubts and discontents were to my father directly, and I don’t think she let him in on whatever alternative life she might have been dreaming about during those times. pg. 59

- We wanted a modern partnership that suited us both. He saw marriage as the loving alignment of two people who could lead parallel lives but without forgoing any independent dreams or ambitions. For me, marriage was more like a full-on merger, a reconfiguring of two lives into one, with the well-being of a family taking precedence over any one agenda or goal. pg. 150,

- We were learning to adapt, to knit ourselves into a solid and forever form of us. Even if we were the same two people we’d always been, the same couple we’d been for years, we now had new labels, a second set of identities to wrangle. He was my husband. I was his wife. We’d stood up at church and said it out loud, to each other and to the world. It did feel as if we owed each other new things. pg. 183

Fertility Challenges

- It turns out that even two committed go-getters with a deep love and a robust work ethic can’t will themselves into being pregnant. Fertility is not something you conquer. Rather maddeningly, there’s no straight line between effort and reward. pg. 199

- Miscarriage is lonely, painful, and demoralizing almost on a cellular level. When you have one, you will likely mistake it for a personal failure, which it is not. Or a tragedy, which, regardless of how utterly devastating it feels in the moment, it also is not….What nobody tells you is that miscarriage happens all the time, to more women than you’d ever guess, given the relative silence around it. pg. 200,

- I wanted a family and Barack wanted a family, too, and now here I was alone in the bathroom of our apartment, trying, in the name of all that want, to screw up the courage to plunge a syringe into my thigh….It was maybe then that I felt a first flicker of resentment involving politics and Barack’s unshakable commitment to the work. Or maybe I was just feeling the acute burden of being female. Either way, he was gone and I was here, carrying the responsibility. I sensed already that the sacrifices would be more mine than his. pg. 201,

- In the weeks to come, he’d go about his regular business while I went in for daily ultrasounds to monitor my eggs. He wouldn’t have his blood drawn. He wouldn’t have to cancel any meetings to have a cervix inspection. He was doting and invested, my husband, doing what he could do. He read all the IVF literature and would talk to me all night about it, but his only actual duty was to show up at the doctor’s office and provide some sperm. …None of this was his fault, but it wasn’t equal, either, and for any woman who lives by the mantra that equality is important, this can be a little confusing. pg. 201

Expectations

- Failure is a feeling long before it becomes an actual result. It’s vulnerability that breeds with self-doubt and then is escalated, often deliberately, by fear. pg. 51

- But as I’ve said, failure is a feeling long before it’s an actual result. And for me, it felt like that’s exactly what she was planting—a suggestion of failure long before I’d even tried to succeed. She was telling me to lower my sights, which was the absolute reverse of every last thing my parents had ever told me. pg. 75

- As we moved toward Barack’s reelection year in 2012, I felt that I couldn’t and shouldn’t rest. I was still earning my grace. I thought often of what I owed and to whom. I carried a history with me, and it wasn’t that of presidents or First Ladies. I’d never related to the story of John Quincy Adams the way I did to that of Sojourner Truth, or been moved by Woodrow Wilson the way I was by Harriet Tubman. The struggles of Rosa Parks and Coretta Scott King were more familiar to me than those of Eleanor Roosevelt or Mamie Eisenhower. I carried their histories, along with those of my mother and grandmothers. None of these women could ever have imagined a life like the one I now had, but they’d trusted that their perseverance would yield something better, eventually, for someone like me. I wanted to show up in the world in a way that honored who they were. I put this on myself as pressure, a driving need not to screw anything up. p 396

Doubt

- Not enough. Not enough. It was doubt about where I came from and what I’d believed about myself until now. It was like a malignant cell that threatened to divide and divide again, unless I could find some way to stop it. pg. 64

- What I’ve learned is this: All of them [extraordinary and accomplished people—world leaders, inventors, musicians, astronauts, athletes, professors, entrepreneurs, artists and writers, pioneering doctors and researchers] have had doubters. Some continue to have roaring, stadium-sized collections of critics and naysayers who will shout I told you so at every little misstep or mistake. The noise doesn’t go away, but the most successful people I know have figured out how to live with it, to lean on the people who believe in them, and to push onward with their goals. pg. 75

- Still, it was impossible to be a black kid at a mostly white school and not feel the shadow of affirmative action. You could almost read the scrutiny in the gaze of certain students and even some professors, as if they wanted to say, “I know why you’re here.” These moments could be demoralizing, even if I’m sure I was just imagining some of it. It planted a seed of doubt. Was I here merely as part of a social experiment? pg. 88

- Confidence, I’d learned then, sometimes needs to be called from within. I’ve repeated the same words to myself many times now, through many climbs. Am I good enough? Yes I am. pg. 310

Ambition

- I was still privately and at all times focused on the agenda. Beneath my laid-back college-kid demeanor, I lived like a half-closeted CEO, quietly but unswervingly focused on achievement, bent on checking every box. My to-do list lived in my head and went with me everywhere. I assessed my goals, analyzed my outcomes, counted my wins. If there was a challenge to vault, I’d vault it. One proving ground only opened onto the next. Such is the life of a girl who can’t stop wondering, Am I good enough? and is still trying to show herself the answer. pg. 97

- All this inborn confidence was admirable, of course, but honestly, try living with it. For me, coexisting with Barack’s strong sense of purpose—sleeping in the same bed with it, sitting at the breakfast table with it—was something to which I had to adjust, not because he flaunted it, exactly, but because it was so alive. In the presence of his certainty, his notion that he could make some sort of difference in the world, I couldn’t help but feel a little bit lost by comparison. His sense of purpose seemed like an unwitting challenge to my own. pg. 140,

- … I was deeply, delightfully in love with a guy whose forceful intellect and ambition could possibly end up swallowing mine. I saw it coming already, like a barreling wave with a mighty undertow. I wasn’t going to get out of its path—I was too committed to Barack by then, too in love—but I did need to quickly anchor myself on two feet. pg. 141

- And this I know for sure about my husband: You don’t dangle an opportunity in front of him, something that could give him a wider field of impact, and expect him just to walk away. Because he doesn’t. He won’t. pg. 205

- Our decision to let Barack’s career proceed as it had—to give him the freedom to shape and pursue his dreams—led me to tamp down my own efforts at work. Almost deliberately, I’d numbed myself somewhat to my ambition, stepping back in moments when I’d normally step forward. I’m not sure anyone around me would have said I wasn’t doing enough, but I was always aware of everything I could have followed through on and didn’t. pg. 224

- Since I’d known him, it seemed to me that Barack had always had his eyes on some far-off horizon, on his notion of the world as it should be. Just for once, I wanted him to be content with life as it was. pg. 236

- We’d lived with other people’s expectations so long that they were almost embedded in every conversation we had. Barack’s potential sat with our family at the dinner table. Barack’s potential rode along to school with the girls and to work with me. It was there even when we didn’t want it to be there, adding a strange energy to everything. pg. 236

- What I hoped was that at some point Barack himself would put an end to the speculation, declaring himself out of contention and directing the media gaze elsewhere. But he didn’t do this. He wouldn’t do this. He wanted to run. He wanted it and I didn’t. pg. 238,

- For better or worse, I’d fallen in love with a man with a vision who was optimistic without being naive, undaunted by conflict, and intrigued by how complicated the world was. pg. 239,

The “Swerve”

[The “swerve” is what Michelle Obama calls the moment when one (either consciously or subconsciously) decides to search for and fulfil one’s true meaning or purpose in life. It is the moment when they decide to stray from traditionally or societally approved life or career paths, and try to discover their own unique purpose in life]

- This may be the fundamental problem with caring a lot about what others think: It can put you on the established path—the my-isn’t-that-impressive path—and keep you there for a long time. Maybe it stops you from swerving, from ever even considering a swerve, because what you risk losing in terms of other people’s high regard can feel too costly. pg. 101

- Suzanne’s sudden death had awakened me to the idea that I wanted more joy and meaning in my life. I couldn’t continue to live with my own complacency. pg. 142

- I both credited and blamed Barack for the confusion. “If there were not a man in my life constantly questioning me about what drives me and what pains me,” I wrote in my journal, “would I be doing it on my own?” pg. 142

- And with that, I unloaded my feelings. I told her that I wasn’t happy with my job, or even with my chosen profession—that I was seriously unhappy, in fact. I told her about my restlessness, how I was desperate to make a major change but worried about not making enough money if I did. My emotions were raw. I let out another sigh. “I’m just not fulfilled,” I said. pg. 144

- It was possible, I knew, to live on two planes at once—to have one’s feet planted in reality but pointed in the direction of progress….You got somewhere by building that better reality, if at first only in your own mind. Or as Barack had put it that night, you may live in the world as it is, but you can still work to create the world as it should be. pg. 428,

- In retrospect I see now that this was my swerve. In that moment, without saying a word, I’d signed on for a lifetime of us, and a lifetime of this. pg. 428

Order vs Chaos

- …I was someone who liked things to be neat and planned in advance, and from what I could tell, there seemed to be nothing especially neat about a life in politics. pg. 73

- Until now, I’d constructed my existence carefully, tucking and folding every loose and disorderly bit of it, as if building some tight and airless piece of origami. I had labored over its creation. I was proud of how it looked. But it was delicate. …I think now it’s why I guarded myself so carefully, why I still wasn’t ready to let him in. He was like a wind that threatened to unsettle everything. pg. 115

- Chaos agitated me, but it seemed to invigorate Barack. He was like a circus performer who liked to set plates spinning: If things got too calm, he took it as a sign that there was more to do. He was a serial over-committer, I was coming to understand, taking on new projects without much regard for limits of time and energy. pg. 181

- My goals mostly involved maintaining normalcy and stability, but those would never be Barack’s. …One yin, one yang. I craved routine and order, and he did not. He could live in the ocean; I needed the boat. pg. 224,

- There was also much that couldn’t be planned for, a larger unruliness that paced the borders of our every day. When you’re married to the president, you come to understand quickly that the world brims with chaos, that disasters unfurl without notice. Forces seen and unseen stand ready to tear into whatever calm you might feel. The news could never be ignored: pg. 371

- I tried to think back and remember how it was that my life had forked away from the predictable, control-freak fantasy existence I’d envisioned for myself—the one with the steady salary, a house to live in forever, a routine to my days. At what point had I chosen away from that? When had I allowed the chaos inside? pg. 427

The Compounding Effect of Advocacy and Early Intervention in Education

- If you’d had a head start at home, you were rewarded for it at school, deemed “bright” or “gifted,” which in turn only compounded your confidence. The advantages aggregated quickly. pg. 25

- Now that I’m an adult, I realize that kids know at a very young age when they’re being devalued, when adults aren’t invested enough to help them learn. Their anger over it can manifest itself as unruliness. It’s hardly their fault. They aren’t “bad kids.” They’re just trying to survive bad circumstances. pg. 29

- But as my luck in life seemed only to snowball from there, I thought more about the twenty or so kids who’d been marooned in that classroom, stuck with an uncaring and unmotivated teacher. I knew I was no smarter than any of them. I just had the advantage of an advocate. I thought about this more often now that I was an adult, especially when people applauded me for my achievements, as if there weren’t a strange and cruel randomness to it all. Through no fault of their own, those second graders had lost a year of learning. I’d seen enough at this point to understand how quickly even small deficits can snowball, too. pg. 187

- I’d been lucky to have parents, teachers, and mentors who’d fed me with a consistent, simple message: You matter. As an adult, I wanted to pass those words to a new generation. It was the message I gave my own daughters, who were fortunate to have it reinforced daily by their school and their privileged circumstances, and I was determined to express some version of it to every young person I encountered. I wanted to be the opposite of the guidance counselor I’d had in high school, who’d blithely told me I wasn’t Princeton material. pg. 416

Mentorship and Opportunity

- Public Allies was all about promise—finding it, nurturing it, and putting it to use. It was a mandate to seek out young people whose best qualities might otherwise be overlooked and to give them a chance to do something meaningful. pg. 187

- But their faces were hopeful, and now so was I. For me it was a strange, quiet revelation: They were me, as I’d once been. And I was them, as they could be. The energy I felt thrumming in that school had nothing to do with obstacles. It was the power of nine hundred girls striving. pg. 348

- If I was the first at some of these things, I wanted to make sure that in the end I wasn’t the only—that others were coming up behind me. pg. 385

- I remembered them all, every person who’d ever waved me forward, doing his or her best to inoculate me against the slights and indignities I was certain to encounter in the places I was headed—all those environments built primarily for and by people who were neither black nor female. pg. 385

- Later, during my time at Public Allies, I saw the benefits of more formal mentoring firsthand. I knew from my own life experience that when someone shows genuine interest in your learning and development, even if only for ten minutes in a busy day, it matters. It matters especially for women, for minorities, for anyone society is quick to overlook. pg. 386

Privilege

- But my first months at Whitney Young gave me a glimpse of something that had previously been invisible—the apparatus of privilege and connection, what seemed like a network of half-hidden ladders and guide ropes that lay suspended overhead, ready to connect some but not all of us to the sky. pg. 66,

- Their trust in the world seemed infinite, their forward progress in it entirely assured. pg. 81

- [At Princeton] We were protected, cocooned, catered to. A lot of kids, I was coming to realize, had never in their lifetimes known anything different. pg. 81,

- I tried not to feel intimidated when classroom conversation was dominated by male students, which it often was. Hearing them, I realized that they weren’t at all smarter than the rest of us. They were simply emboldened, floating on an ancient tide of superiority, buoyed by the fact that history had never told them anything different. pg. 88

Politics

- There were days, weeks, and months when I hated politics. And there were moments when the beauty of this country and its people so overwhelmed me that I couldn’t speak. pg. 7

- When I was in first grade, a boy in my class punched me in the face one day, his fist coming like a comet, full force and out of nowhere. …Only when I was in my early forties and trying to help get my husband elected president would I think back to that day in the lunch line in first grade, remembering how confusing it was to be ambushed, how much it hurt to get socked in the face with no warning at all. pg. 277

- I was getting worn out, not physically, but emotionally. The punches hurt, even if I understood that they had little to do with who I really was as a person. …I was exhausted by the meanness, thrown off by how personal it had become, and feeling, too, as if there were no way I could quit. …I am telling you, this stuff hurt. pg. 293

- We were standing before a giant, jubilant mass of Americans who were also palpably reflective. What I heard was relative silence. It seemed almost as if I could make out every face in the crowd. There were tears in many eyes. Maybe the calmness was something I imagined, or maybe for all of us, it was just a product of the late hour. It was almost midnight, after all. And everyone had been waiting. We’d been waiting a long, long time. pg. 308

Discrimination

- These were highly intelligent, able-bodied men who were denied access to stable high-paying jobs, which in turn kept them from being able to buy homes, send their kids to college, or save for retirement. It pained them, I know, to be cast aside, to be stuck in jobs that they were overqualified for, to watch white people leapfrog past them at work, sometimes training new employees they knew might one day become their bosses. And it bred within each of them at least a basic level of resentment and mistrust: You never quite knew what other folks saw you to be. pg. 46

Race/Racism/Belonging [Princeton]

- But even today, with white students continuing to outnumber students of color on college campuses, the burden of assimilation is put largely on the shoulders of minority students. In my experience, it’s a lot to ask. pg. 83

- At Princeton, I needed my black friends. We provided one another relief and support. So many of us arrived at college not even aware of what our disadvantages were. pg. 83

- It was like stepping onstage at your first piano recital and realizing that you’d never played anything but an instrument with broken keys. Your world shifts, but you’re asked to adjust and overcome, to play your music the same as everyone else. pg. 84

- This is doable, of course—minority and underprivileged students rise to the challenge all the time—but it takes energy. … It requires effort, an extra level of confidence, to speak in those settings and own your presence in the room. pg. 84

- I didn’t, in fact, have many white friends at all. In retrospect, I realize it was my fault as much as anyone’s. I was cautious. I stuck to what I knew. It’s hard to put into words what sometimes you pick up in the ether, the quiet, cruel nuances of not belonging—the subtle cues that tell you to not risk anything, to find your people and just stay put. pg. 84

Race/Racism/Belonging [Politics]

- The scrutiny of Barack would be extra intense, the lens always magnified. We knew that as a black candidate he couldn’t afford any sort of stumble. He’d have to do everything twice as well. pg. 248

- Beginning in May, Barack had been assigned Secret Service protection. It was the earliest a presidential candidate had been given a protective detail ever, a full year and a half before he could even become president-elect, which said something about the nature and the seriousness of the threats against him. pg. 258,

- Barack and I were now too well-known to be rendered invisible, but if people saw us as alien and trespassing, then maybe our potency could be drained….The message seemed often to get telegraphed, if never said directly: These people don’t belong. pg. 291

- I was female, black, and strong, which to certain people, maintaining a certain mind-set, translated only to “angry.” It was another damaging cliché, one that’s been forever used to sweep minority women to the perimeter of every room, an unconscious signal not to listen to what we’ve got to say. pg. 293,

- It’s remarkable how a stereotype functions as an actual trap. How many “angry black women” have been caught in the circular logic of that phrase? When you aren’t being listened to, why wouldn’t you get louder? If you’re written off as angry or emotional, doesn’t that just cause more of the same? pg. 293

- As the only African American First Lady to set foot in the White House, I was “other” almost by default. If there was a presumed grace assigned to my white predecessors, I knew it wasn’t likely to be the same for me. pg. 309

- For more than six years now, Barack and I had lived with an awareness that we ourselves were a provocation….Our presence in the White House had been celebrated by millions of Americans, but it also contributed to a reactionary sense of fear and resentment among others. The hatred was old and deep and as dangerous as ever. pg. 430,

Twice as Good

- There’s an age-old maxim in the black community: You’ve got to be twice as good to get half as far. pg. 322,

- There were so few of us minority kids at Princeton, I suppose, that our presence was always conspicuous. I mainly took this as a mandate to overperform, to do everything I possibly could to keep up with or even plow past the more privileged people around me. Just as it had been at Whitney Young, my intensity was spawned at least in part by a feeling of I’ll show you. If in high school I’d felt as if I were representing my neighborhood, now at Princeton I was representing my race. Anytime I found my voice in class or nailed an exam, I quietly hoped it helped make a larger point. pg. 89

- I’d learned through the campaign stumbles that I had to be better, faster, smarter, and stronger than ever. My grace would need to be earned. pg. 310

- I was humbled and excited to be First Lady, but not for one second did I think I’d be sliding into some glamorous, easy role. Nobody who has the words “first” and “black” attached to them ever would. I stood at the foot of the mountain, knowing I’d need to climb my way into favor. pg. 310

- The president-elect, I learned, is given access to $100,000 in federal funds to help with moving and redecorating, but Barack insisted that we pay for everything ourselves, using what we’d saved from his book royalties. As long as I’ve known him, he’s been this way: extra-vigilant when it comes to matters of money and ethics, holding himself to a higher standard than even what’s dictated by law. pg. 321,

- As the first African American family in the White House, we were being viewed as representatives of our race. Any error or lapse in judgment, we knew, would be magnified, read as something more than what it was. pg. 322

- Though I was thought of as a popular First Lady, I couldn’t help but feel haunted by the ways I’d been criticized, by the people who’d made assumptions about me based on the color of my skin. To this end, I rehearsed my speeches again and again using a teleprompter set up in one corner of my office. I pushed hard on my schedulers and advance teams to make sure every one of our events ran smoothly and on time. I pushed even harder on my policy advisers to continue growing the reach of Let’s Move! and Joining Forces. I was focused on not wasting any of the opportunities I now had, but sometimes I had to remind myself just to breathe. pg. 396

(Female) Friendship

- I like the idea of being rigorous about friendship. pg. 392

- Friendships between women, as any woman will tell you, are built of a thousand small kindnesses…swapped back and forth and over again. pg. 392

- My friends made me whole, as they always have and always will. They gave me a lift anytime I felt down or frustrated or had less access to Barack. They grounded me when I felt the pressures of being judged, having everything from my choice of nail-polish color to the size of my hips dissected and discussed publicly. And they helped me ride out the big, unsettling waves that sometimes hit without notice. pg. 393

Political Identity

- The truth was that Washington confused me, with its decorous traditions and sober self-regard, its whiteness and maleness, its ladies having lunch off to one side. At the heart of my confusion was a kind of fear, because as much as I hadn’t chosen to be involved, I was getting sucked in. I’d been Mrs. Obama for the last twelve years, but it was starting to mean something different. At least in some spheres, I was now Mrs. Obama in a way that could feel diminishing, a missus defined by her mister. pg. 234

- I knew the stereotype I was meant to inhabit, the immaculately groomed doll-wife with the painted-on smile, gazing bright-eyed at her husband, as if hanging on every word. This was not me and never would be. I could be supportive, but I couldn’t be a robot. pg. 246

- I was becoming known. And I was becoming known for being someone’s wife and as someone involved with politics, which made it doubly and triply weird…I had little time to think much about it, but quietly I worried that as my visibility as Barack Obama’s wife rose, the other parts of me were dissolving from view. pg. 257,

Time Management and Relationship Problems

- But time was now officially an issue for us. If Barack’s disregard for punctuality had once been something I’d gently teased him about, it was now a straight-up aggravation. pg. 217

- We live by the paradigms we know. …In Barack’s childhood, his father disappeared and his mother came and went. She was devoted to him but never tethered to him, and as far as he was concerned, there was nothing wrong in this approach. pg. 218

- I feared that the path he’d chosen for himself—and still seemed so clearly committed to pursuing—would end up steamrolling our every need. pg. 218

- At home, our frustrations began to rear up often and intensely. Barack and I loved each other deeply, but it was as if at the center of our relationship there were suddenly a knot we couldn’t loosen. pg. 219

- This turned out to be the big revelation for me about counseling: No validating went on. No sides were taken. When it came to our disagreements, Dr. Woodchurch would never be the deciding vote. pg. 220

Love and Romance

- He was looking at me curiously, with the trace of a smile. “Can I kiss you?” he asked. And with that, I leaned in and everything felt clear. pg. 117

- Barack intrigued me. He was not like anyone I’d dated before, mainly because he seemed so secure. He was openly affectionate. He told me I was beautiful. He made me feel good. pg. 118

- I love talking to my husband across a small table in a low-lit room. I always have, and I expect I always will. Barack is a good listener, patient and thoughtful. I love how he tips his head back when he laughs. I love the lightness in his eyes, the kindness at his core. pg. 351

Sexism

- Dominance, even the threat of it, is a form of dehumanization. It’s the ugliest kind of power. .. Women endure entire lifetimes of these indignities—in the form of catcalls, groping, assault, oppression. These things injure us. They sap our strength. Some of the cuts are so small they’re barely visible. Others are huge and gaping, leaving scars that never heal. Either way, they accumulate. We carry them everywhere, to and from school and work, at home while raising our children, at our places of worship, anytime we try to advance. pg. 442

The Importance of Music

- My family was loaded with musicians and music lovers, especially on my mother’s side. pg. 16

- We celebrated most major life events at Southside’s house, which meant that over the years we unwrapped Christmas presents to Ella Fitzgerald and blew out birthday candles to Coltrane. pg. 17

- According to my mother, as a younger man Southside had made a point of pumping jazz into his seven children, often waking everyone at sunrise by playing one of his records at full blast. pg. 17

- To me, Southside was as big as heaven. And heaven, as I envisioned it, had to be a place full of jazz. pg. 17

Statements through Fashion

- Sometime during Barack’s campaign, people had begun paying attention to my clothes. pg. 360

- It seemed that my clothes mattered more to people than anything I had to say. pg. 361,

- This stuff got me down, but I tried to reframe it as an opportunity to learn, to use what power I could find inside a situation I’d never have chosen for myself. pg. 361

- It was a thin line to walk. I was supposed to stand out without overshadowing others, to blend in but not fade away. As a black woman, too, I knew I’d be criticized if I was perceived as being showy and high end, and I’d be criticized also if I was too casual. pg. 362

- For me, my choices were simply a way to use my curious relationship with the public gaze to boost a diverse set of up-and-comers. pg. 362

- Optics governed more or less everything in the political world, and I factored this into every outfit. It required time, thought, and money—more money than I’d spent on clothing ever before. pg. 362

The Role of First Lady of the United States

- There is no handbook for incoming First Ladies of the United States. It’s not technically a job, nor is it an official government title. It comes with no salary and no spelled-out set of obligations. pg. 309

- As I saw it, I didn’t actually have to do anything. No job description meant no job requirements, and this gave me the freedom to choose my agenda. I wanted to ensure any effort I made helped advance the new administration’s larger goals. pg. 322

- A First Lady’s power is a curious thing—as soft and undefined as the role itself. And yet I was learning to harness it. pg. 403

- Tradition called for me to provide a kind of gentle light, flattering the president with my devotion, flattering the nation primarily by not challenging it. I was beginning to see, though, that wielded carefully the light was more powerful than that. pg. 403

Barack Obama’s Vision

- But listening to Barack, I began to understand that his version of hope reached far beyond mine: It was one thing to get yourself out of a stuck place, I realized. It was another thing entirely to try and get the place itself unstuck. pg. 125

- He wasn’t a preacher, but he was definitely preaching something—a vision. He was making a bid for our investment. The choice, as he saw it, was this: You give up or you work for change. pg. 125

- “Do we settle for the world as it is, or do we work for the world as it should be?” …It was as close as I’d come to understanding what motivated Barack. The world as it should be. pg. 125,

- What he was building, I see now, was a vision—and not a small one, either….He’d been working at this thing, quietly and meticulously, as long as I’d known him. And now maybe the size of the audience would finally match the scope of what he believed to be possible. He’d been ready for that call. All he had to do was speak. pg. 228

Recommended Reading

You may also enjoy the following books:

A Promised Land by Barack Obama (2020)

Have you read this book? What did you think? Share your thoughts and ideas with me!

If you found this summary helpful, just click here to share it