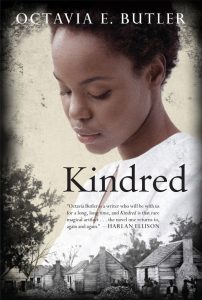

Kindred, by Octavia E. Butler

Publisher : Doubleday (1979)

ISBN-13 :978-0807083697

Rating:

Quick Thoughts

Octavia Butler’s Kindred is a fantastic novel that vividly describes the horrors and legacy of slavery. It demonstrates the true meaning of courage and grace under extreme conditions, and describes what it means to survive and endure. It shows the imprint that America’s past history of slavery continues to bear upon its modern present.

Summary

In 1976, a contemporary young African-African woman living in suburban Los Angeles is repeatedly pulled into the past, specifically to Antebellum Maryland, about thirty years prior to the Civil War. Through the shared connection with one of her (white) ancestors, she must deal with the horrors of slavery, while trying to ensure that her family’s bloodline survives and endures.

Characters

Edana “Dana” Franklin

Dana is a young African-American woman, and the novel’s narrator and protagonist. She is first called to Rufus on June 9th 1976, which also happens to be her 26th birthday. She is strong, intelligent, and fiercely independent. In her own timeline, Dana is also a writer. On her sixth and final trip to the past, Dana loses her left arm.

Rufus Weylin

He is Dana’s white ancestor. He has red hair and green eyes. He is obsessed with Alice, and his rape of her instigates Alice’s enslavement. After she becomes his property, he coerces Alice into a physically and sexually abusive relationship. Rufus and Alice have two children – Joe and Hagar, the latter of whom becomes Dana’s ancestor. Rufus’ link with Dana is what pulls Dana into the past whenever his life is endangered.

Kevin Franklin

He is a writer and Dana’s white husband. They first meet when Dana is 22 and Kevin is 34. When he is accidentally also transported to the past with Dana, Kevin uses his privilege as a white man to protect Dana, and also assist in the slavery abolition movement.

Alice Jackson (born Alice Greenwood)

Alice is Dana’s enslaved ancestor. Initially born free, she is enslaved and becomes Rufus’ property when she tries (and fails) to help Isaac Jackson, a slave (and her husband), to escape. She is the object of Rufus’ obsession. After she becomes Rufus’s property, he beats and rapes her in a coercive relationship. She bears him two children – Joe and Hagar (Dana’s ancestor). She eventually hangs herself out of despair when Rufus lies to her about selling her children as a punishment for trying to escape the plantation.

Tom Weylin

Tom Weylin is Rufus’s father, and the master of the Weylin Plantation, which is located in Maryland. He is vicious and brutal, quick to use his fists and whips on his slaves. He also neglects, beats and whips his own son. But, by the standards of the day, he is comparatively fair-minded because he honors his promises to blacks and white alike.

Hagar Weylin Blake

Born in February 1831, she is the daughter of Rufus and Alice, and Dana’s ancestor. It is Hagar’s birth that Dana must ensure. Like Dana, she is dark-skinned. She marries Oliver Blake, and dies in 1880, having had seven children and some grandchildren. She begins a family Bible that is passed down through the generations; it records all of Hagar’s family genealogy, including births, deaths, and marriages.

Nigel

A slave who is Rufus’s companion. He is around the same age as Rufus. He marries Carrie and has three sons with her.

Luke

Nigel’s father. He is a slave and works as a driver on the plantation, keeping the field hands in line; he is a black overseer. He is later sold by Tom Weylin.

Sarah

She is the head cook on the plantation, and in charge of household affairs. When Dana first meets her, she is middle-aged. She is described as handsome, tall and heavy-set. She has four children but all of them, except Carrie (who is mute), are sold away from her. Her placid demeanour hides her deep anger at the Weylins for the sale of her children.

Carrie

Sarah’s daughter. She is mute, and very intelligent. She later marries Nigel and together, they have a son, Jude, and two other children.

Isaac Jackson

He is Alice’s slave husband, and owned by Judge Holman, a nearby plantation owner. After beating up Rufus as revenge for raping Alice, Isaac tries to escape. He is caught by patrollers, and beaten severely. His ears are cut off, and he is sold away to a plantation in the South.

Tess

A field slave. She is passed from Tom Weylin to Jake Edwards, the white overseer. She is eventually sold.

Margaret Weylin

Rufus’ mother. She spoils Rufus. She is nervous and fussy, and poorly-educated. She is described as pretty, with bright red hair and green eyes. She spends most of her days on the plantation doing nothing of consequence, while much of the household is run by Sarah. After the death of her twin babies, she is said to have gone crazy and retreats to her sister’s house in Baltimore to recuperate. After Tom Weylin’s death, she returns to the plantation many years later, a laudanum/opium addict.

Miss Hannah

Tom Weylin’s deceased first wife. She initially owns the Weylin property that becomes Tom’s upon marriage and her death. She is described as educated, and a real lady.

Joe Weylin

Alice and Rufus’ son. He is light-skinned, with red hair, like his father. He is Hagar’s older brother. Dana teaches him to read and he is bright and eager to learn.

Sam James

He is a field slave who expresses some interest in Dana. He also asks Dana to teach his siblings to read. Rufus sells Sam out of jealousy.

Analysis

The book is structured around six trips that Dana makes into the past, each centered around the situation that endangers Rufus. For instance, the first chapter, “The River” is named after the river that almost drowns Rufus until Dana shows up to save him.

Themes

Obsessive Love

Rufus harbors a possessive, destructive, and obsessive love for Alice. It drives him to rape her, enraging and provoking Alice’s slave husband, Isaac. Alice’s failed attempt to then help Isaac to escape is what leads to her own enslavement.

Alice becomes Rufus’ property; a literal possession. As Dana realizes, “He spoke out of love for the girl—a destructive love, but a love, nevertheless.” (158)

Rufus’ unrequited love for Alice is one-sided. A relationship between a slave and a slave owner in the antebellum south is unlikely to have a happy ending. “ I was beginning to realize that he loved the woman—to her misfortune. There was no shame in raping a black woman, but there could be shame in loving one.” (131)

But how real is this love? Rufus has no compunction beating Alice, raping her, or having her whipped. Moreover, he desires Alice, regardless of her consent. “Maybe I can’t ever have that—both wanting, both loving. But I’m not going to give up what I can have.”. (175)

“You know, Dana,” he said softly, “when you sent Alice to me that first time, and I saw how much she hated me, I thought, I’ll fall asleep beside her and she’ll kill me. She’ll hit me with a candlestick. She’ll set fire to the bed. She’ll bring a knife up from the cookhouse … “I thought all that, but I wasn’t afraid. Because if she killed me, that would be that. Nothing else would matter. But if I lived, I would have her. And, by God, I had to have her.”. (278)

This is a love that is destructive for both Rufus and Alice. Rufus seeks a reciprocal relationship. “He wants me to like him,” she said with heavy contempt. “Or maybe even love him.!” (251).

Rufus also harbors, to a lesser extent, a similar obsessive love for Dana. He views Dana as Alice’s more educated, intellectual counterpart. Both women are two halves of a whole. And Rufus intends to have both halves.

“It was that destructive single-minded love of his. He loved me. Not the way he loved Alice, thank God. He didn’t seem to want to sleep with me. But he wanted me around—someone to talk to, someone who would listen to him and care what he said, care about him. (194)

Rufus lies to Alice about having mailed her letters to Kevin, asking him to return to the plantation. Later, with a gun, Rufus even tries to prevent Kevin and Dana from leaving. He would prefer Dana to remain with him in his own time. He admires Dana for her strength, intelligence, and resourcefulness. As Alice remarks, “He likes me in bed, and you out of bed, and you and I look alike if you can believe what people say.” (247)

As Alice remarks, “He’ll never let any of us go,” she said. “The more you give him, the more he wants.” (254). Rufus’ voraciousness leads to his decision to assault Dana. In the process, Rufus loses his life and Dana loses her right arm. Her lost arm becomes a permanent and physical reminder of the dangers of obsession.

Violence and Brutality

Kindred demonstrates the horrors and brutality the enslaved characters experience. There are beatings, whippings, hangings, mutilations, dog attacks, and more. Dana, a modern Black woman, is unused to the casual violence and brutality on a slave plantation.

“The man tackled me and brought me down hard. At first, I lay stunned, unable to move or defend myself even when he began hitting me, punching me with his fists. I had never been beaten that way before—would never have thought I could absorb so much punishment without losing consciousness.” (37)

Besides physical violence, there is also mental, emotional, and psychological violence. Tom Weylin, the plantation master, sells people on a whim, or to keep the enslaved in line, or to satisfy his wife’s wishes for new furniture. He does this with no regard for existing family relationships or blood ties.

“But Carrie was a useful young woman. Not only did she work hard and well herself, not only had she produced a healthy new slave, but she had kept first her mother, and now her husband in line with no effort at all on Weylin’s part. I didn’t want to find out how much Rufus had learned from his father’s handling of her.. pg. 182.

This is a different, perhaps even more cruel kind of violence. As Dana observes, “Kevin, you don’t have to beat people to treat them brutally.” (104)

“He wasn’t a monster at all. Just an ordinary man who sometimes did the monstrous things his society said were legal and proper. (142)

Rape

“I would have taken better care of her than any field hand could. I wouldn’t have hurt her if she hadn’t just kept saying no.” pg. 129

Rape and sexual violence are prevalent throughout Kindred. Dana’s family’s survival and her own very existence is dependent upon an act of rape. Also, not only must Dana save Rufus’ life, but she is complicit in his desire to coerce Alice into a sexual relationship.

“Go to her. Send her to me. I’ll have her whether you help or not. All I want you to do is fix it so I don’t have to beat her. You’re no friend of hers if you won’t do that much!” (176)

For Dana’s ancestor, Hagar, to be born, Rufus must be allowed to assault Alice.

Alice’s choices, as an enslaved woman, are limited. She is Rufus’ property, with no power to deny him. As Dana tells her, “Well, it looks as though you have three choices. You can go to him as he orders; you can refuse, be whipped, and then have him take you by force; or you can run away again.” (179)

Rape is also an ever-present fact of life for the other enslaved women. Tess, the field hand, is casually passed around from master to plantation overseer. “You do everything they tell you,” she wept, “and they still treat you like a old dog. Go here, open your legs; go there, bust your back. What they care! I ain’t s’pose to have no feelin’s!” (196)

Sarah the cook bears children for the plantation’s former owner. Dana herself fears the threat of rape from Rufus. That fear is eventually realized and results in his destruction.

“He could drive me to a kind of unthinking fury. Somehow, I couldn’t take from him the kind of abuse I took from others. If he ever raped me, it wasn’t likely that either of us would survive.(194)

Many women of that time, unlike Dana, had no option of freedom.

The Corrupting Influence of Slavery

Butler makes the case that slavery as an institution is damaging to both black and white people. It is the enslaved blacks who seem to have the most respect for family and blood ties. The white characters – Tom Weylin, Rufus, and Margaret – seem isolated, unhappy, and alienated. Tom beats and neglects his own son. He has affairs with slave women, a fact his wife pretends not to notice. Tom Weylin doesn’t even acknowledge the several enslaved children he fathers on the plantation. Tom Weylin’s lack of acknowledgement, his neglect and indifference to his own children might be a byproduct of the brutality required to engage in the slave trade.

The corrupt influence of plantation life coarsens Rufus, who begins as a more thoughtful and respectful character. As a young boy, he befriends Nigel and Alice. But, ultimately, Rufus steps into his birthright as a young white slaveowner, raping Alice, and continuing to enslave his former childhood friend. He is corrupted by the institution of slavery. “Maybe he’ll never be as hard as his father was, but he’s a man of his time.” (262)

Butler makes the case that slavery corrupts the enslavers, leaving them broken, in many different ways. Tom Weylin turns brutal, his wife Margaret develops an opium addiction, and Rufus turns into a lonely, unhappy slave owner with a drinking problem.

“Why do you keep trying to kill yourself?” I said softly. I hadn’t expected an answer so I was surprised when he spoke quietly. “Most of the time, living just isn’t worth the trouble.” (221)

Rufus wants Alice’s love, and that cannot happen while she is his property, unable to fully consent and take part in a relationship based on a foundation of equality and mutual respect. “I didn’t want to just drag her off into the bushes,” said Rufus. “I never wanted it to be like that. But she kept saying no. I could have had her in the bushes years ago if that was all I wanted.” (131).

Rufus wants the relationship that Kevin and Dana share:

“I know you, Dana. You want Kevin the way I want Alice. And you had more luck than I did because no matter what happens now, for a while he wanted you too. Maybe I can’t ever have that—both wanting, both loving. But I’m not going to give up what I can have.” (175)

This inability to achieve this goal warps Rufus. His grief over Alice’s choice to commit suicide rather than continue as his mistress is what destroys him.

“Abandonment. The one weapon Alice hadn’t had. Rufus didn’t seem to be afraid of dying. Now, in his grief, he seemed almost to want death. But he was afraid of dying alone, afraid of being deserted by the person he had depended on for so long.” (279)

Dana also worries whether her husband Kevin will be corrupted by the almost unlimited power he holds as a white man in a slave owning society .

A place like this would endanger him in a way I didn’t want to talk to him about. If he was stranded here for years, some part of this place would rub off on him. No large part, I knew. But if he survived here, it would be because he managed to tolerate the life here. He wouldn’t have to take part in it, but he would have to keep quiet about it. Free speech and press hadn’t done too well in the ante bellum South. Kevin wouldn’t do too well either. The place, the time would either kill him outright or mark him somehow. I didn’t like either possibility. (78)

Dana wonders about Kevin:

This place, this time, hadn’t been any kinder to him than it had been to me. But what had it made of him? What might he be willing to do now that he would not have done before? (198)

Power & Control

Dana has no control over the force that links her to Rufus and pulls her back into the past. “We come from a future time and place. I don’t know how we get here. We don’t want to come. We don’t belong here. But when you’re in trouble, somehow you reach me, call me, and I come—although as you can see now, I can’t always help you.” (60)

She has no control over the frequency and duration of her visits into the past. She is summoned whenever Rufus’ life is endangered, and she can only leave when she feels her life is in peril. “Then … Rufus’s fear of death calls me to him, and my own fear of death sends me home.” (47)

She can’t even be sure that Rufus’ death will send her back to her own time and place.

“But how do I come home? Is the power mine, or do I tap some power in him? All this started with him, after all. I don’t know whether I need him or not. And I won’t know until he’s not around.” (267)

Similarly, as a black woman in the slave-owning south, Dana has no control over how people perceive and treat her. Her skin color is the most salient part of her, and dominates how she is treated – as a slave. “A slave was a slave. Anything could be done to her.” (282)

Meanwhile, Rufus uses the threat of harm to others to control Dana. “He had already found the way to control me—by threatening others. That was safer than threatening me directly, and it worked. It was a lesson he had no doubt learned from his father” (182) And, for the other enslaved people on the plantation, threats of violence to themselves or their families,or the fear of separation is enough to keep them in line or prevent them from running away.

And the nature of slavery means the violence is one-sided. The slaves cannot fight back; they lack any agency, power or control over their lives. To resist is to risk a severe whipping, certain death, or the separation from one’s family. Slavery is an institution that encompasses all aspects of the enslaved’s life, with violence, power, and control of the enslaved body at its core. As Dana observes, due to her status as both a woman and a black person, “Kevin, I’m not going to be in any fair fights.” (44)

And Alice describes her own powerlessness, “…I get so mad … I get so mad I can taste it in my mouth. And you’re the only one I can take it out on—the only one I can hurt and not be hurt back.” (180)

Blood Ties & Kinship

This book is literally about family and blood ties. It’s about your kin. Dana and Rufus are connected by blood. So are Alice and Dana. Hagar, the product of Alice and Rufus’s relationship, is the child who becomes Dana’s ancestor on her maternal side.

Alice Greenwood. How would she marry this boy? Or would it be marriage? And why hadn’t someone in my family mentioned that Rufus Weylin was white? If they knew. Probably, they didn’t. Hagar Weylin Blake had died in 1880, long before the time of any member of my family that I had known. No doubt most information about her life had died with her. At least it had died before it filtered down to me. There was only the Bible left…. Hagar had filled pages of it with her careful script. There was a record of her marriage to Oliver Blake, and a list of her seven children, their marriages, some grandchildren … Then someone else had taken up the listing. So many relatives that I had never known, would never know. (22)

Dana is a living legacy of the mixed ties between slave owner and slave. Her family’s history is a familiar one to many African Americans. It is a reminder of the untold stories that live in the family backgrounds of many African Americans.

Butler uses time travel to literally pull the present into the past; a reminder that the actions of the past still echo and have an affect in the future. Time travel is used as a device to render the past in vivid, living color. Kindred pulls Dana into the past, so she can confront the horrors of slavery. Her and Kevin’s experience puts her ancestor’s actions into greater historical understanding and context.

Rufus and Dana share a connection that repeatedly brings them together. Dana is summoned to the past whenever Rufus’ life is endangered. She discerns that she needs to ensure that Rufus lives long enough to at least father Hagar, “Was that why I was here? Not only to insure the survival of one accident-prone small boy, but to insure my family’s survival, my own birth….If I was to live, if others were to live, he must live. I didn’t dare test the paradox. (23)

Is it their blood ties? Something else?

Some matching strangeness in us that may or may not have come from our being related. Still, now I had a special reason for being glad I had been able to save him. After all … after all, what would have happened to me, to my mother’s family, if I hadn’t saved him? (23)

And, it’s all made worse by the fact that for Dana to be born, she has to allow Rufus to continue to hurt Alice.

Maybe that was why we didn’t hate each other. We could hurt each other too badly, kill each other too quickly in hatred. He was like a younger brother to me. Alice was like a sister. It was so hard to watch him hurting her—to know that he had to go on hurting her if my family was to exist at all. pg. 194

Dana is brought into the past to ensure that history is not changed. She is unable to change the past. Just like her ancestors, Dana can only bear witness and endure, for the sake of her family.

Survival and Compromise Under Slavery

Part of Butler’s goal in this book is to put to rest the idea that African Americans were too weak or too ignorant to resist enslavement.

“Strength. Endurance. To survive, my ancestors had to put up with more than I ever could. Much more. (48)

Butler demonstrates that the enslaved had incredible strength and courage. They had to make terrible and impossible choices, endure horrific conditions, in order for future generations to have a chance of a better life. She depicts this as an act of tremendous self control, sacrifice, and courage.

There were no good choices for black people under slavery, and people had to do what they needed to do to survive. They endured pain, torture, threats, family separation, daily humiliation, and sometimes, even death. The actions of enslaved African Americans should be evaluated in that historical context.

Butler uses the character of Sarah to convey the complicated layers beneath the seemingly placid acceptance of enslavement. Sarah refuses to even discuss the possibility of freedom. Butler demonstrates the need for more sympathy for characters like Sarah.

She had done the safe thing—had accepted a life of slavery because she was afraid. She was the kind of woman who might have been called “mammy” in some other household. She was the kind of woman who would be held in contempt during the militant nineteen sixties. The house-nigger, the handkerchief-head, the female Uncle Tom—the frightened powerless woman who had already lost all she could stand to lose, and who knew as little about the freedom of the North as she knew about the hereafter. (155)

Sarah’s seeming placidity and acceptance hides an extreme grief and rage. She is not untouched.

The expression in her eyes had gone from sadness—she seemed almost ready to cry—to anger. Quiet, almost frightening anger. Her husband dead, three children sold, the fourth defective, and her having to thank God for the defect. She had reason for more than anger. pg. (76)

As a slave, Sarah has no good choices. She can only try to survive and protect her remaining child. She remains on the plantation to protect her family.

Similarly, while initially born free, Alice is enslaved by Rufus and kept as his mistress. Rufus’s desire for her marks her as an object of contempt by some of the other slaves. She is trapped, with no good choices.

“She went to him. She adjusted, became a quieter more subdued person. She didn’t kill, but she seemed to die a little.” (181)

The only thing to do is to try to survive and hold on to her sense of self.

[Alice] forgave him nothing, forgot nothing, hated him as deeply as she had loved Isaac. I didn’t blame her. But what good did her hating do? She couldn’t bring herself to run away again or to kill him and face her own death. She couldn’t do anything at all except make herself more miserable. She said, “My stomach just turns every time he puts his hands on me!” But she endured. Eventually, she would bear him at least one child. (194)

In the end, after the perceived loss of her children, Alice commits suicide. In death, she is finally free of Rufus and her life of enslavement. Alice compromises until there is finally nothing left to compromise for.

“If your black ancestors had felt that way, you wouldn’t be here,” said Kevin. “I told you when all this started that I didn’t have their endurance. I still don’t. Some of them will go on struggling to survive, no matter what. I’m not like that.” (266)

The Present and The Past

Upon returning to their home in suburban Los Angeles in 1976, both Kevin and Dana have trouble adjusting. The past feels more vivid and real . After spending five years in the past, Kevin is aged by his experience, his accent changes, and he has trouble remembering how to drive a car. He finds modern life different, easier, “Everything is so soft here,” he said, “so easy …” (207)“

Dana also feels discombobulated by her trips back and forth between present and past:

Today and yesterday didn’t mesh. I felt almost as strange as I had after my first trip back to Rufus—caught between his home and mine. (121)

I felt as though I were losing my place here in my own time. Rufus’s time was a sharper, stronger reality. The work was harder, the smells and tastes were stronger, the danger was greater, the pain was worse … Rufus’s time demanded things of me that had never been demanded before, and it could easily kill me if I did not meet its demands. (205)

And, in the end, in the process of killing Rufus, Dana loses her left arm.

From the elbow to the ends of the fingers, my left arm had become a part of the wall. I looked at the spot where flesh joined with plaster, stared at it uncomprehending. It was the exact spot Rufus’s fingers had grasped. I pulled my arm toward me, pulled hard. And suddenly, there was an avalanche of pain, red impossible agony! And I screamed and screamed.

It is a literal physical reminder that the horrors of the past can still carry into the present. Although Dana manages to escape the past, she does not come away unscathed. The past finds a way to shape the future, and there is always a price to pay.

Acceptance and Conditioning

Dana and Kevin are surprised by how effortlessly they each fall into their prescribed roles on a slave plantation. It surprises Dana how easily her independence is stripped away, and how quickly people can be conditioned to accept their roles in life.

- “The ease. Us, the children … I never realized how easily people could be trained to accept slavery.” (105)

- I tried to get away from my thoughts, but they still came. See how easily slaves are made? they said. (191)

- My back had already begun to ache dully, and I felt dully ashamed. Slavery was a long slow process of dulling. (197)

- Once—God knows how long ago—I had worried that I was keeping too much distance between myself and this alien time. Now, there was no distance at all. When had I stopped acting? Why had I stopped? (239)

Interracial Relationships

Kindred is so obviously about race. Butler explores the theme of race by placing the central characters into interracial relationships. Kevin and Dana are in an interracial relationship based on love and respect. In modern 1976, they are married, and connect with each other based on their shared interests and love of writing. Despite this, both of them are ostracized by their families due to their relationship. They suffer for their love in the present.

And, in the past, Dana must pretend to be Kevin’s slave, while she worries over the impact that living in antebellum times will have on him. She also struggles to convey their different experiences of living in the past. Although they both travel to the past, their skin color separates them, and places them on extremely different trajectories. She tells Kevin:

“You might be able to go through this whole experience as an observer,” I said. “I can understand that because most of the time, I’m still an observer. It’s protection. It’s nineteen seventy-six shielding and cushioning eighteen nineteen for me. But now and then, like with the kids’ game, I can’t maintain the distance. I’m drawn all the way into eighteen nineteen, and I don’t know what to do. I ought to be doing something though. I know that.” pg. 105

Kevin’s experience as a white man, and Dana’s experience as a black woman in the antebellum south can never be the same.

“I thought, that could be me—standing there with a rope around my neck waiting to be led away like someone’s dog!” I stopped, looked down at him, then went on softly. “I’m not property, Kevin. I’m not a horse or a sack of wheat. If I have to seem to be property, if I have to accept limits on my freedom for Rufus’s sake, then he also has to accept limits—on his behavior toward me. He has to leave me enough control of my own life to make living look better to me than killing and dying.” (266)

Although Kevin disapproves of slavery, and tries to protect Dana, his skin color and male privilege makes it hard for him to fully understand and share in Dana’s experiences. He is initially excited about the prospect of spending time in the past:

“This could be a great time to live in,” Kevin said once. “I keep thinking what an experience it would be to stay in it—go West and watch the building of the country, see how much of the Old West mythology is true.” “West,” I said bitterly. “That’s where they’re doing it to the Indians instead of the blacks!” He looked at me strangely. He had been doing that a lot lately. (100)

Kevin initially sees the prospect of living in the past as an exciting adventure. To Dana, the past is nothing but horror.

In antebellum Maryland, Rufus and Alice are also in a nonconsensual interracial relationship between slave and slave owner. There will be no romance or conventional future based on a position of freedom or equality between the two. Rufus bemoans his fate. He says “If I lived in your time, I would have married her. Or tried to.” (131) He believes he loves Alice, although his actions belie our modern understanding of romance, equality, and partnership.

Dana and Rufus are also in an interracial relationship. They are kindred! Rufus is Dana’s ancestor, and the connection between the two is one based on blood.

I looked over at the boy who would be Hagar’s father. There was nothing in him that reminded me of any of my relatives. Looking at him confused me. But he had to be the one. There had to be some kind of reason for the link he and I seemed to have. (22)

Butler never explains the supernatural force that links Rufus to Dana, but it is surely not a coincidence that they are connected by blood. Dana’s existence is a reminder of the history of interracial mixing between white and black Americans. Her relationship with Kevin represents the hope for a better representation of that mixed legacy.

Top Quotes

- I was beginning to realize that he loved the woman—to her misfortune. There was no shame in raping a black woman, but there could be shame in loving one. pg. 131

- “… you don’t have to beat people to treat them brutally.” pg. 104

- I felt as though I were losing my place here in my own time. Rufus’s time was a sharper, stronger reality. The work was harder, the smells and tastes were stronger, the danger was greater, the pain was worse … Rufus’s time demanded things of me that had never been demanded before, and it could easily kill me if I did not meet its demands. pg. 205

- My back had already begun to ache dully, and I felt dully ashamed. Slavery was a long slow process of dulling. pg. 197

- “If your black ancestors had felt that way, you wouldn’t be here,” said Kevin. “I told you when all this started that I didn’t have their endurance. I still don’t. Some of them will go on struggling to survive, no matter what. I’m not like that.” pg. 266